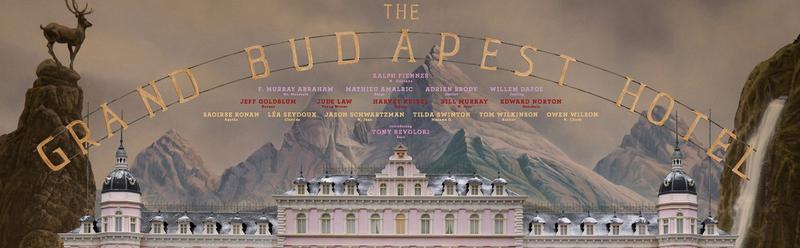

The Grand Budapest Hotel

Wes Anderson got me thinking seriously about cinema for the first time. The fourteen year-old me was absolutely blown away by The Life Aquatic, despite being arguably one of his weaker films. When I saw Bill Murray stride around the cutaway of his ship I couldn’t believe that someone would break the rules I’d become accustomed to. It didn’t feel like a joke but it was funny somehow. How could this be? There’s no cue to laugh? It’s easy to write these off as pointless quirks (especially in this film) but at that age I’d never seen anything like it.

His work is still just as surprising and unique with every film he makes. The Grand Budapest Hotel is no different. It’s the story of an author (Tom Wilkinson) recounting the tale of a visit to the titular hotel, wherein he meets the owner of the establishment (F Murray Abraham). The owner then proceeds to tell his own story of how the hotel came into his hands. This story is where most of the film occurs, with Ralph Fiennes being our protagonist who steals a work of art left to him in a will that the owner’s family don’t want to give up. Sounds complicated on paper, it’s easy to follow on screen.

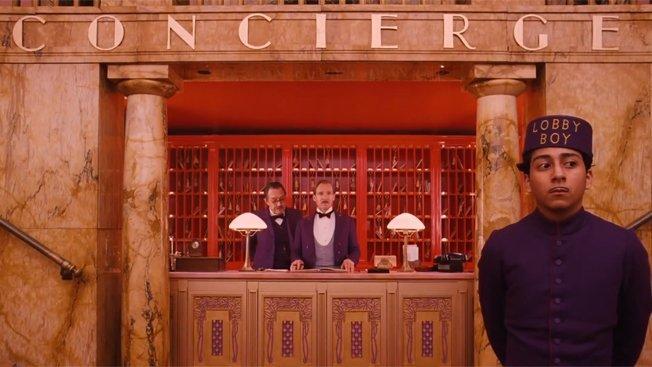

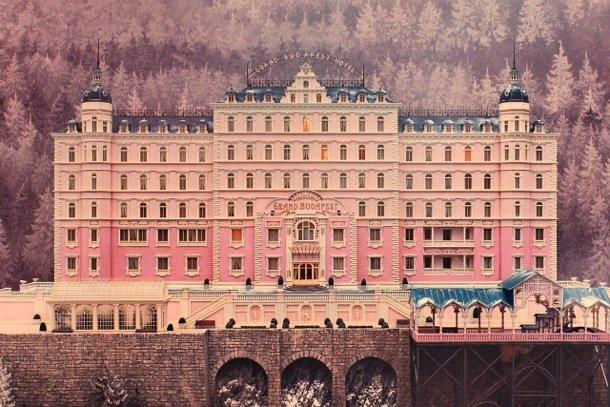

This is a masterpiece on so many levels. The set design is so typical of his style, yet it’s still like no other film. It oozes character, and makes the film an other worldly experience. The set serves the story to an extent where the movie wouldn’t work without it. There’s detail in every frame, and it’s beautiful. The camera moves are also noteworthy. We get the usual elaborate long takes that follow the characters around, but Anderson also introduces quick turns and snappy zoom-ins. It’s fun to watch, and adds to the visual aesthetic.

In a time when watching a season of House of Cards is the activity du jour, it’s a surprise to me that this film got made at all. It’s something to be looked at and enjoyed, rather than consumed and thrown away. It’s a lost art, but Anderson understands it and takes it forwards even if the world doesn’t think it needs him to.